Our Services

Our consultants combine the expertise of community and economic development practitioners and researchers. This gives us an advantage in developing and providing evidence of a wide range of successful practices that can be applied to community projects.

FROM BIG CITIES TO SMALL TOWNS IN RURAL AREAS, WE HAVE THE EXPERTISE THAT CAN HELP YOU SUCCEED.

Arts-Based Development: Building Creative Communities

Research Parks: Building Engaged Business and Research Communities

Business Incubation and Entrepreneurship:

Building Entrepreneurial Communities

Organizational Network Analysis: Building Innovative Communities, Government, and Corporations

Food Hubs and Cooperatives: Building Food Communities

Feasibility Studies, Strategic Plans, Action Plans, Community Research, Implementation Support

Makerspaces: Building New Manufacturing Businesses

Workshops and Courses

Arts-Based Development: Building Creative Communities

Arts and culture can be powerful community assets. Arts-based economic and community development is often cited as a means to improve quality of life for communities while attracting jobs, tourists, and new residents. The arts sector is also a competitive tool that can generate income and tax revenues while strengthening the regional economy, education, civic engagement, and youth development. Arts centers, arts incubators, arts and music festivals, cultural tourism, makerspaces, and a variety of other combined strategies can be used to support and build local arts economies, but they should also strive to be self-supporting whenever possible. While there are a lot of trendy ideas and jargon going around, how do you figure out what will work best in your community?

Artists are an appropriate target for occupational clustering strategies in economic development. Rural communities that make the effort of refurbishing older buildings to host artists or arts centers are able to attract new creative residents while prompting import substitution to support local economies, and these arts centers often become the centerpieces for downtown revitalization. In addition to selling their work and spending in their community, resident artists participate in cultural events that draw both local residents and tourists, and many serve as art teachers, helping to develop the next generation of local artists or train talented adults in the region. A UK study of the arts in community economic development found that the principal benefit for many communities lay in the capacity of arts industries to generate employment during recession and restructuring. On the smaller scale of annual arts events, a study of 2,586 rural arts and cultural festivals in Australia demonstrated a strong association between these economically modest activities and major local economic benefits, both direct and indirect. The presence of artists and cultural opportunities in a community also increases quality of life, drawing both retirees and professional occupations as new residents.

Do you want to learn more? We are internationally recognized experts in the evaluation and application of evidence-based strategies for the development of creative entrepreneurial communities and arts-based development programs. We have advised national nonprofits as well as state, county, and local governments on arts-based development programs. Contact us today and we’ll match you up with one of our consultants.

Business Incubation and Entrepreneurship: Building Entrepreneurial Communities

Many business incubators have failed since they started to become trendy in the 1980s, mostly as a result of poor planning, unrealistic goals, inexperienced management, or a lack of community support. However, successful incubator models and best practices have been demonstrated since 1959, although they have to be customized for different communities. Retaining incubated businesses in the community is also important, but often poorly managed. Whether it’s arts incubators or technology incubators, our approach uses lessons learned from best practices, current research, and our own direct experience in building, running, and advising incubator programs.

Starting in 1959, the first phase of incubators revolved around the idea that small businesses needed space, access to office equipment, and shared administrative support. The second phase of business incubators in the 1980s merged this concept with training in business skills, mentoring, access to growth capital, and peer networking offered in a wider variety of office and industrial spaces. Space rental continued to be the main revenue source to keep these incubators operating. Some incubators received a small amount of equity in their incubated companies, while many did not, and most operated under a nonprofit business model. For-profit incubators appeared in the 1990s, but few remain, although these few continue to do well because they are in special environments like Silicon Valley where there is enough demand and population density to support them. Accelerator programs also appeared in the 1990s as an alternative mechanism for investors to put small amounts of funding into a startup company to see if it would become viable within a few months to justify a larger investment. The accelerator concept has often been confused with incubators, which provide various kinds of support over a longer time frame.

When a community invests funding, time, and energy into an incubator to support the growth of small businesses, they usually do so in the hopes that successfully growing companies will remain in the community once they graduate from the incubator program, but will often find that these companies move away to the cities where their investors or better markets with more workers are located. Small towns and rural places suffer the most when this occurs. Does this have to happen? This is usually a failure on the part of the incubator management and the operating philosophy of the incubator. Community building inside and outside the incubator is necessary to retain these growing businesses and build their local networks, yet business retention programs and incentives in cities tend to focus on big companies while overlooking the small businesses that may predominate in their environment.

Do you want to learn more? We have advised state, county, and local governments on incubator development, as well as having direct experience in building and operating incubators ourselves. Contact us today with your details and we’ll match you up with one of our consultants.

Food Hubs and Cooperatives: Building Food Communities

Food hubs and co-ops often run on thin margins and can take a long time to become self-sustaining if they don’t fail before then. One solution is to combine food hub aggregation and marketing strategies with related but higher-margin services, such as commercial kitchens for value-added food processing, contract processing, rental, classes, and incubation of food entrepreneur businesses. Another approach is to combine the co-op with a connected restaurant, food delivery services for seniors and children, and other strategies that can also draw federal or state funds to help these programs get started. Food networks and collaborations can also be built up around these programs for stronger community development.

According to the USDA, there were 2,047 agricultural cooperatives in the United States in 2015 grossing over $212 billion, serving over 1.9 million members and employing 136,285 full-time and 51,004 part-time employees. While these figures tend to be inflated by the largest cooperatives, this demonstrates potential for growth in co-ops over long periods of time.

Where cooperatives differ is in their governance structure, their motivations, and in the nature of the value being created. Cooperatives are normally launched to solve some type of local problem facing the agricultural industry. During the age of agricultural modernization, the “problem” centered around the purchase of equipment and facilities, such as feed mills, grain silos, and farm equipment. Producer-oriented cooperatives emerged when farmers banded together to collectively purchase equipment and facilities that were too expensive or inefficient for any one farmer to afford, including infrastructure like electricity and telephone in the early 20th Century. Many facilities, pieces of equipment, and infrastructure could be shared and jointly managed, minimizing the price of purchase to the farmer while preserving their ability to benefit from the equipment. Everyday supplies like feed, seed, and fertilizer could also be purchased at a lower price through volume discounts if groups of farmers purchased these items collectively. Collective bargaining could be used to negotiate better insurance rates, establish credit unions, and create affordable housing.

These successful practices eventually moved into collaborative marketing and sales of agricultural products. Virtual brands appeared, and some of the most recognized American brands are actually cooperatives of dispersed growers, such as Tillamook, Blue Diamond, Oceans Spray, Sunkist, and Land O’Lakes.

Food hubs are a more recent type of seller-oriented cooperative. The goal of a food hub is to aggregate, or pool together, agricultural products from diverse sources so that they can be sold in higher volumes at competitive prices. Small farms have limited access to major markets, and must often cultivate buyers on their own, or sell at popular venues like farmers markets and local produce distributors. By aggregating the produce of many small farmers together, these farms can achieve a level of consistency that no one farmer can achieve on his/her own. Larger clients like grocery chains, food distributors, processors, and major restaurants demand a high level of consistency at a reasonable cost that can typically only be reached in larger volumes. As a result, aggregation empowers smaller farmers to access more markets, which can raise their on-farm profitability.

Do you want to learn more? We have advised county and local governments on the planning and creation of food co-ops and related strategies supporting local farmers and food business entrepreneurs. Contact us today and we’ll match you up with one of our consultants.

Research Parks: Building Engaged Business and Research Communities

Research park planning and design generally takes the approach that real estate is everything–put up some buildings and let the magic happen–and yet many research parks sit empty. Where is the magic? The intent behind the co-location of industry and research partners in a research park, or science park, is to foster collaboration and innovation, which may also lead to the commercialization of new technologies. This is magic created by people through their interactions, but companies will not magically interact just by being located next to each other, and being next to a university is not a formula for instant success, either. Community development is necessary. What can you do?

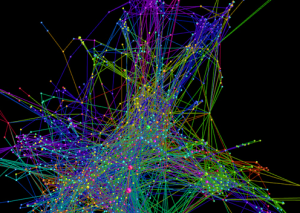

Under the older linear model of innovation, new technologies would flow out of universities, national laboratories, or corporate laboratories to the marketplace in a straight-line process. Traditional research park metrics intended to measure innovation under the linear model will often look like they’re failing. Counting the annual number of licensing agreements for intellectual property, number of startups using that IP, or number of jobs created, provide a picture of the corner of a painting rather than the whole painting. Newer non-linear innovation models understand that innovation is messy and harder to track, embedded in formal and informal networks of relationships as part of an iterative system. Active research park management is required to enable innovation communities that facilitate collaboration and information flow, while also creating social spaces and social opportunities that build networks.

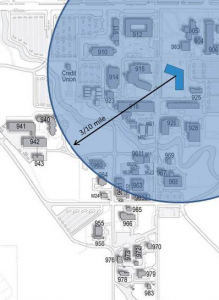

In a research park where the intent is to co-locate industry partners with researchers to commercialize new technologies, knowledge diffusion is more likely to happen through informal interactions in public spaces, bars, restaurants, and hotel lobbies. Parks that lack these facilities are being left behind, while re-engineered parks such as Research Triangle are reviving themselves by creating these spaces along with housing and other mixed-use facilities for a live-work-play environment. There is also often a lack of understanding about the social and information-flow effects of proximity, despite considerable research on designs for interaction that identify reasonable limits on interaction spaces in office interiors and the spacing between buildings. If your office is more than 150 feet away from mine, I’m probably not going to interact with you much outside of formal meetings. If your coffee machine is in or near your office, I’m probably not going to bump into you informally, either. If your office is half a mile away from mine on campus, I probably won’t even think about you. And there is plenty of research to demonstrate that phones, Internet access, e-mail, texting, and video communications aren’t very helpful for collaborative interactions, either. In fact, the people we most often call, e-mail, or text are the same people we see in-person each day. If you want an innovative environment, you need opportunities for informal and face-to-face contact.

Many early parks were essentially property developments intended to support research-based commercial activity, allowing universities to sell or lease space adjacent to their campuses where researchers might commercialize their work or firms might locate for access to academic expertise. Although early parks preferred to recruit established technology companies to their parks, a primary goal of current parks is to help local businesses to grow, so many American parks now include business incubation space with support services for entrepreneurs. This acknowledges research evidence that it is easier to establish and grow local businesses rather than hoping to attract big companies to relocate their headquarters to your location.

Are you planning a research park? Are you redesigning your research park? Are you trying to establish an innovation park, business park, or industrial park where you want to foster creativity, innovation, interaction, and incubation? We’d be happy to talk to you about it.

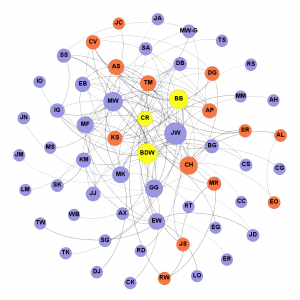

Organizational Network Analysis: Building Innovative Communities, Government, Nonprofits, and Corporations

The formation of cooperative partnerships or networks is a commonly used tactic for addressing community needs and goals. The intent is to enhance the capacity of a community and its organizations to bring a wide variety of stakeholders together to address problems and deliver necessary services. However, the development of these networks and partnerships among multiple organizations can be difficult to create or sustain over time. As an example, many nonprofits feel that they are in competition with others and do not want to share resources. City and county governments may have similar concerns. Corporations may not feel it is worth their time to engage with other organizations in a community. Each of these entities also views their networks from a single perspective, just as individuals do, making it hard to understand the functioning of the larger community network or how it might benefit them. The same thing happens within the internal networks of organizations.

Relational network analysis, commonly referred to as social network analysis, is a means to quantify and explain social relationships at a deeper level than is typically used to study and manage organizations or collective social behavior. Tools such as organizational charts are good for showing agreed-upon lines of authority in a group, but not for showing how work actually gets done, how information moves through a group, or how key people serve to expand the network as facilitators or block information flow as communication bottlenecks. Network analysis can also identify the people who are the most powerful or influential in a network–the org chart may indicate that the CEO is in charge when the reality is that the most significant influencer in the organization is someone else entirely. It is often the case that informal relationships in social networks are the hidden shortcuts to getting things done.

Managerial approaches to improving collaboration usually involve a blanket approach of increased communication, leading to more meetings for everyone due to a lack of sufficient information about key leverage points in the social network that would efficiently improve information flow. While community initiatives are often developed through the creation of new social connections, as well as the knowledge and resources that individuals carry, broad attempts at managing network processes, without a clear understanding of obstacles and leverage points within a network structure, can have the negative result of network fragmentation.

Do you want to learn more? If you want to make your network or organization more effective with improved communications and productivity, contact us with your details and we’ll match you up with one of our consultants.

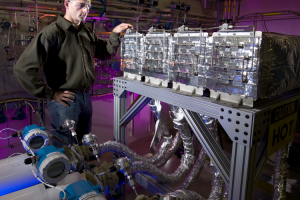

MAKERSPACES: Building NEW MANUFACTURING BUSINESSES

Although the makerspace term first appeared in 2005 with the introduction of MAKE Magazine, it was 2011 before the term became more popular. A “maker” is a person who makes things. “Makerspaces” are shared community facilities for the public to make things with high-end manufacturing equipment and other tools for multiple crafts. Laser cutters, 3-D printers, and computerized machine tools are often provided along with training in how to use them. These spaces are typically used by both professional craftspeople and hobbyists, and the interaction of these users creates a supportive environment for learning, prototyping, experimentation, collaboration, and community building. For communities interested in expanding their options for economic development, creation and support of a makerspace provides the opportunity to launch new manufacturing businesses started by “maker-entrepreneurs” while upgrading local workforce skills and building community. Although it is not commonly seen yet, this strategy is particularly effective when a business incubation program is offered along with makerspace access to help start or grow new businesses. Makerspaces also offer inclusiveness and the potential to be a key driver for the achievement of a city’s equity goals.

Considerations regarding the creation of a new makerspace, outside of the facility and equipment expense, include whether such a program can be self-supporting in a particular community. Many makerspaces have been started by hobbyists who later learn that they don’t know how to build or run a business, so the makerspaces fail. In some communities, the local/regional market for users may not be large enough to support the program. Cases like these suggest a need for scaling or hybrid strategies that can meet multiple community needs while becoming financially viable. For example, depending on the community, a business incubator strategy with rental spaces and mentoring might be combined with a makerspace to help launch and grow new businesses. A culinary arts program with a shared kitchen might be combined with a makerspace to help new food businesses get started or allow them to expand.

Are you planning to develop a makerspace in your community? Do you want to learn more? We have advised nonprofits and governments on makerspace and incubator development, as well as having direct experience in building and operating incubators ourselves. Contact us today with your details and we’ll match you up with one of our consultants.

Feasibility Studies, Strategic Plans, Action Plans, Community Research, Implementation Support

The CICD team views community planning processes as opportunities to partner with local stakeholders for insights into local values, priorities, and culture for increased project acceptance and greater likelihood of success. Our plans reflect diverse community input, rigorous data collection/analysis, partnering with existing organizations and assets, and substantial interaction with local project leaders. The CICD team has both the advanced training and the practical experience to deliver on economic and community development strategies that engage the community while providing a path to sustainability.

While we can provide a broad array of examples from programs, ideas, and processes that have worked elsewhere, each community is different. Solutions drawn from local engagement that are enhanced with external research are most likely to meet the needs and aspirations of the community with regard to local history and capacity to implement the plans we help create. We also operate in a neutral and objective manner, allowing us to view the local scene with new eyes, evaluate risks and assets, avoid competition with existing programs or services, and negotiate a path among conflicting viewpoints when necessary.

Are you preparing for a new community venture or planning activity? Do you need an action plan to move your strategies forward? We are internationally recognized experts in the evaluation and application of evidence-based strategies for the development of creative entrepreneurial communities We have developed feasibility studies, strategic plans, tactical action plans, and community research for nonprofits and for local, county, regional, and state governments. As practitioners, we also have direct experience in building and managing community programs. Contact us today with your questions or ideas and we’ll match you up with one of our consultants.

WORKSHOPS AND COURSES

We are currently in the process of developing our workshops for 2018, which will be listed on our Workshops and Courses page as they become available.

We are also developing an online certificate program in community and economic development for Sam Houston State University in Texas. We expect the first of these Continuing Education courses to become available in Fall 2018, and you do not have to be a resident of Texas to participate. We will post registration and tuition information for this program on our Workshops and Courses page.